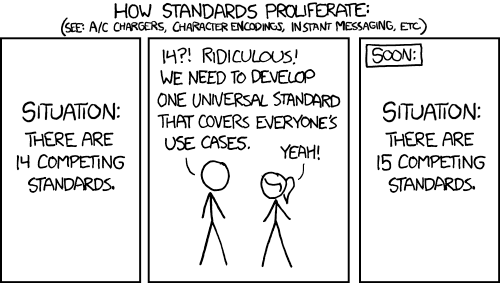

I wasn’t really sure I even wanted to write this up — mostly because there are some limitations in MCP that make things a little… awkward. But I figured someone else is going to hit the same wall eventually, so here we are.

If you’re trying to use OAuth 2.0 with MCP, there’s something you should know: it doesn’t support the full OAuth framework. Not even close.

MCP only works with the default well-known endpoints:

/.well-known/openid-configuration/.well-known/oauth-authorization-server

Before we get going, let me write this in the biggest and most awkward text I can find.

Run the Device Flow outside of MCP, then inject the token into the session manually.

And those have to be hosted at the default paths, on the same domain as the issuer. If you’re using split domains, custom paths, or a setup where your metadata lives somewhere else (which is super common in enterprise environments)… tough luck. There’s no way to override the discovery URL.

It also doesn’t support other flows like device_code, jwt_bearer, or anything that might require pluggable negotiation. You’re basically stuck with the default authorization code flow, and even that assumes everything is laid out exactly the way it expects.

So yeah — if you’re planning to hook MCP into a real-world OAuth deployment, just be aware of what you’re signing up for. I wish this part of the protocol were a little more flexible, but for now, it’s pretty locked down.

Model Context Protocol (MCP) is an emerging standard for AI model interaction that provides a unified interface for working with various AI models. When implementing OAuth with an MCP test server, we’re dealing with a specialized scenario where authentication and authorization must accommodate both human users and AI agents.

This technical guide covers the implementation of OAuth 2.0 in an MCP environment, focusing on the unique requirements of AI model authentication, token exchange patterns, and security considerations specific to AI workflows.

Prerequisites

Before implementing OAuth with your MCP test server:

- MCP Server Setup: A running MCP test server (v0.4.0 or later)

- Developer Credentials: Client ID and secret from the MCP developer portal

- OpenSSL: For generating key pairs and testing JWT signatures

- Understanding of MCP’s Auth Requirements: Familiarity with MCP’s auth extensions for AI contexts

Section 1: MCP-Specific OAuth Configuration

1.1 Registering Your Application

MCP extends standard OAuth with AI-specific parameters:

curl -X POST https://auth.modelcontextprotocol.io/register \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{

"client_name": "Your AI Agent",

"client_type": "ai_service", # MCP-specific client type

"grant_types": ["authorization_code", "client_credentials"],

"redirect_uris": ["https://your-domain.com/auth/callback"],

"scopes": ["mc:inference", "mc:fine_tuning"], # MCP-specific scopes

"ai_metadata": { # MCP extension

"model_family": "your-model-family",

"capabilities": ["text-generation", "embeddings"]

}

}'

1.2 Understanding MCP’s Auth Flows

MCP supports three primary OAuth flows:

- Standard Authorization Code Flow: For human users interacting with MCP via UI

- Client Credentials Flow: For server-to-server AI service authentication (sucks, doesn’t work, even the work arounds, don’t do it)

- Device Flow: For headless AI environments

Section 2: Implementing Authorization Code Flow

2.1 Building the Authorization URL

MCP extends standard OAuth parameters with AI context:

from urllib.parse import urlencode

auth_params = {

'response_type': 'code',

'client_id': 'your_client_id',

'redirect_uri': 'https://your-domain.com/auth/callback',

'scope': 'openid mc:inference mc:models:read',

'state': 'anti-csrf-token',

'mcp_context': json.dumps({ # MCP-specific context

'model_session_id': 'current-session-uuid',

'intended_use': 'interactive_chat'

}),

'nonce': 'crypto-random-string'

}

auth_url = f"https://auth.modelcontextprotocol.io/authorize?{urlencode(auth_params)}"

2.2 Handling the Callback

The MCP authorization server will return additional AI context in the callback:

@app.route('/auth/callback')

def callback():

auth_code = request.args.get('code')

mcp_context = json.loads(request.args.get('mcp_context', '{}')) # MCP extension

token_response = requests.post(

'https://auth.modelcontextprotocol.io/token',

data={

'grant_type': 'authorization_code',

'code': auth_code,

'redirect_uri': 'https://your-domain.com/auth/callback',

'client_id': 'your_client_id',

'client_secret': 'your_client_secret',

'mcp_context': request.args.get('mcp_context') # Pass context back

}

)

# MCP tokens include AI-specific claims

id_token = jwt.decode(token_response.json()['id_token'], verify=False)

print(f"Model Session ID: {id_token['mcp_session_id']}")

print(f"Allowed Model Operations: {id_token['mcp_scopes']}")

Section 3: Client Credentials Flow for AI Services

3.1 Requesting Machine-to-Machine Tokens

import requests

response = requests.post(

'https://auth.modelcontextprotocol.io/token',

data={

'grant_type': 'client_credentials',

'client_id': 'your_client_id',

'client_secret': 'your_client_secret',

'scope': 'mc:batch_inference mc:models:write',

'mcp_assertion': generate_mcp_assertion_jwt() # MCP requirement

},

headers={'Content-Type': 'application/x-www-form-urlencoded'}

)

token_data = response.json()

# MCP includes additional AI context in the response

model_context = token_data.get('mcp_model_context', {})

3.2 Generating MCP Assertion JWTs

MCP requires a signed JWT assertion for client credentials flow:

import jwt

import datetime

def generate_mcp_assertion_jwt():

now = datetime.datetime.utcnow()

payload = {

'iss': 'your_client_id',

'sub': 'your_client_id',

'aud': 'https://auth.modelcontextprotocol.io/token',

'iat': now,

'exp': now + datetime.timedelta(minutes=5),

'mcp_metadata': { # MCP-specific claims

'model_version': '1.2.0',

'deployment_env': 'test',

'requested_capabilities': ['inference', 'training']

}

}

with open('private_key.pem', 'r') as key_file:

private_key = key_file.read()

return jwt.encode(payload, private_key, algorithm='RS256')

Section 4: MCP Token Validation

4.1 Validating ID Tokens

MCP ID tokens include standard OIDC claims plus MCP extensions:

from jwt import PyJWKClient

from jwt.exceptions import InvalidTokenError

def validate_mcp_id_token(id_token):

jwks_client = PyJWKClient('https://auth.modelcontextprotocol.io/.well-known/jwks.json')

try:

signing_key = jwks_client.get_signing_key_from_jwt(id_token)

decoded = jwt.decode(

id_token,

signing_key.key,

algorithms=['RS256'],

audience='your_client_id',

issuer='https://auth.modelcontextprotocol.io'

)

# Validate MCP-specific claims

if not decoded.get('mcp_session_id'):

raise InvalidTokenError("Missing MCP session ID")

return decoded

except Exception as e:

raise InvalidTokenError(f"Token validation failed: {str(e)}")

4.2 Handling MCP Token Introspection

def introspect_mcp_token(token):

response = requests.post(

'https://auth.modelcontextprotocol.io/token/introspect',

data={

'token': token,

'client_id': 'your_client_id',

'client_secret': 'your_client_secret'

}

)

introspection = response.json()

if not introspection['active']:

raise Exception("Token is not active")

# Check MCP-specific introspection fields

if 'mc:inference' not in introspection['scope'].split():

raise Exception("Missing required inference scope")

return introspection

Section 5: MCP-Specific Considerations

5.1 Handling Model Session Context

MCP tokens include session context that must be propagated:

def call_mcp_api(endpoint, access_token):

headers = {

'Authorization': f'Bearer {access_token}',

'X-MCP-Context': json.dumps({

'session_continuity': True,

'model_temperature': 0.7,

'max_tokens': 2048

})

}

response = requests.post(

f'https://api.modelcontextprotocol.io/{endpoint}',

headers=headers,

json={'prompt': 'Your AI input here'}

)

return response.json()

5.2 Token Refresh with MCP Context

def refresh_mcp_token(refresh_token, mcp_context):

response = requests.post(

'https://auth.modelcontextprotocol.io/token',

data={

'grant_type': 'refresh_token',

'refresh_token': refresh_token,

'client_id': 'your_client_id',

'client_secret': 'your_client_secret',

'mcp_context': json.dumps(mcp_context)

}

)

if response.status_code != 200:

raise Exception(f"Refresh failed: {response.text}")

return response.json()

Section 6: Testing and Debugging

6.1 Using MCP’s Test Token Endpoint

curl -X POST https://test-auth.modelcontextprotocol.io/token \

-H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" \

-d "grant_type=client_credentials" \

-d "client_id=test_client" \

-d "client_secret=test_secret" \

-d "scope=mc:test_all" \

-d "mcp_test_mode=true" \

-d "mcp_override_context={\"bypass_limits\":true}"

6.2 Analyzing MCP Auth Traces

Enable MCP debug headers:

headers = {

'Authorization': 'Bearer test_token',

'X-MCP-Debug': 'true',

'X-MCP-Traceparent': '00-0af7651916cd43dd8448eb211c80319c-b7ad6b7169203331-01'

}

Why did this suck so much?

Implementing OAuth with an MCP test server requires attention to MCP’s AI-specific extensions while following standard OAuth 2.0 patterns. Key takeaways:

- Always include MCP context parameters in auth flows

- Validate MCP-specific claims in tokens

- Propagate session context through API calls

- Leverage MCP’s test endpoints during development

For production deployments, ensure you:

- Rotate keys and secrets regularly

- Monitor token usage patterns

- Implement proper scope validation

- Handle MCP session expiration gracefully