Microsoft’s Linux Love Letter: A Necessary Dose of Historical Context

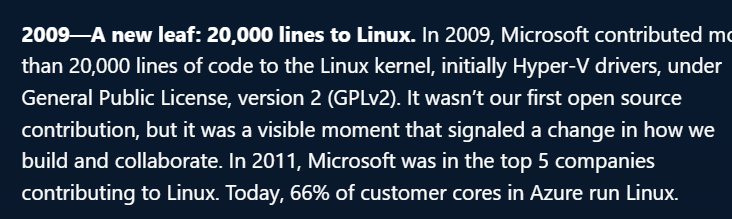

A headline caught my eye recently, one in a long series of similar pieces from Microsoft: a celebratory look back at their 2009 contribution of 20,000 lines of code to the Linux kernel. The narrative is one of a new leaf, a turning point, a company evolving from a closed-source fortress into a collaborative open-source neighbor.

And on its face, that’s a good thing. I am genuinely glad that Microsoft contributes to Linux. Their work on Hyper-V drivers and other subsystems is technically sound and materially benefits users running Linux on Azure. It’s a practical, smart business move for a company whose revenue now heavily depends on cloud services that are, in large part, powered by Linux.

But as I read these self-congratulatory retrospectives, I can’t help but feel a deep sense of whiplash. To present this chapter without the full context of the book that preceded it is not just revisionist; it’s borderline insulting to those of us who remember the decades of hostility.

Let’s not forget what “building and collaborating” looked like for Microsoft before it became convenient.

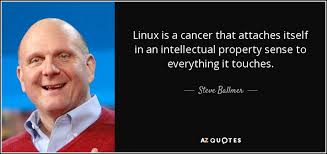

This is the company whose CEO, Steve Ballmer, famously called Linux “a cancer” in 2001. This wasn’t an off-the-cuff remark; it was the public-facing declaration of a deeply entrenched corporate ideology. For years, Microsoft’s primary strategy wasn’t to out-build Linux, but to use its immense market power to strangle it.

They engaged in a brutal campaign of FUD (Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt):

- They threatened patents, suggesting that Linux and other open-source software infringed on hundreds of Microsoft patents, aiming to scare corporations away from adoption.

- They entered into costly licensing agreements with other tech companies, essentially making them pay “protection money” against hypothetical lawsuits.

- They argued that open-source software was an intellectual property-destroying “communist” model that was antithetical to American business.

This was not healthy competition. This was a multi-pronged legal and rhetorical assault designed to kill the project they now proudly contribute to. They didn’t just disagree with open source; they actively tried to destroy it.

So, when Microsoft writes a post that frames their 2009 code drop as a moment that “signaled a change in how we build and collaborate,” I have to ask: what changed?

Did the company have a moral awakening about the virtues of software freedom? Did they suddenly realize the error of their ways?

The evidence suggests otherwise. What changed was the market. The rise of the cloud, which Microsoft desperately needed to dominate with Azure, runs on Linux. Their old strategy of hostility became a direct threat to their own bottom line. They didn’t embrace Linux; they surrendered to its inevitability. The contribution wasn’t a peace offering; it was a strategic necessity. You can’t be the host for the world’s computing if you refuse to support the world’s favorite operating system.

This isn’t to say we shouldn’t accept the contribution. We should. The open-source community has always been pragmatically welcoming. But we should accept it with clear eyes.

Praising Microsoft for its current contributions is fine. Forgetting its history of attempted destruction is dangerous. It whitewashes a chapter of anti-competitive behavior that should serve as a permanent cautionary tale. It allows a corporation to rebrand itself as a “cool, open-source friend” without ever fully accounting for its past actions.

So, by all means, let’s acknowledge the 20,000 lines of code. But let’s also remember the millions of words and dollars spent trying to make sure those lines—and the entire ecosystem around them—would never see the light of day. The true story isn’t one of a change of heart, but a change of market forces. And that’s a history we must never let them forget.