Look, the old ways of auth weren’t built for what’s coming. AI agents don’t live in static sessions or predictable flows—they’re ephemeral, reactive, scattered across clouds, and making decisions faster than your token TTL. So why are we still handing them bearer tokens like it’s 2012? Nothing should be permanent. Context matters. What the agent is doing right now should influence what it’s allowed to do right now. That means proof tied to the moment, not to some long-lived credential you forgot to revoke. It should be rooted in hardware—attested, unforgeable, impossible to rip out and reuse. And above all, it should be decentralized. No single gatekeeper. No single failure point. Trust should move with the agent, like a shadow—provable, portable, disposable. Authentication needs to evolve, or it’ll just be another thing the agents bypass.

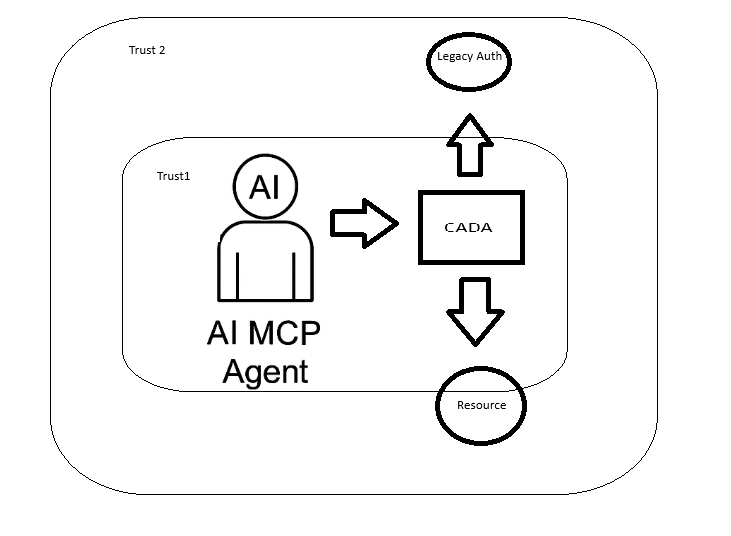

As AI MCP agents evolve into autonomous, multi-tenant actors operating across data planes, trust boundaries, and compute contexts, traditional token-based frameworks like OAuth 2.0 fail to provide the necessary granularity, context-awareness, and runtime verification. CADA introduces a new model for zero-standing privilege, context-aware identity, and attestation-driven trust, leveraging confidential computing and decentralized identity primitives.

Core Pillars

- Decentralized Identity Anchors (DID-A)

- Each MCP agent is assigned a Decentralized Identifier (DID) backed by a verifiable credential (VC).

- The identity is not centrally registered but anchored in a distributed ledger or verifiable key infrastructure (e.g., SIDetree, Sovrin, or ION).

- DIDs resolve to metadata including key rotation history, policies, and agent type (exploratory, monitoring, remediation, etc.).

- Context-Bound Proof-of-Presence Tokens (CB-PoP)

- Instead of bearer tokens, agents use signed ephemeral tokens with embedded context:

- Temporal window (e.g., within the last 30s)

- Location constraints (verified via confidential enclave attestation)

- Input/output scope (model state hashes, data fingerprinting)

- These are validated by services with confidential computing backends using Intel SGX/AMD SEV or AWS Nitro Enclaves.

- Instead of bearer tokens, agents use signed ephemeral tokens with embedded context:

- FIDO2 + TPM/TEE Hardware Anchoring

- Each agent’s execution environment binds its private signing key to a hardware root of trust, such as TPM or TEE.

- Authentication occurs via WebAuthn-style challenges, signed inside a secure enclave, with attestation reports validating runtime integrity.

- Eliminates key export risk and enables remote trust of agent execution context.

- Dynamic Trust Contracts (DTC)

- Each authenticated interaction is governed by a smart contract defining:

- Data access policies

- Audit/tracing rules

- Time-limited execution permissions

- Revocation semantics based on real-time observability inputs

- These contracts are cryptographically signed by the MCP owner and verified prior to execution.

- Each authenticated interaction is governed by a smart contract defining:

- Zero Standing Privilege with Just-In-Time Delegation

- Agents do not persist access tokens.

- Authorization is granted at runtime through delegated trust, using time-bound, task-specific credentials derived from identity and context proof.

Authentication Flow Example

- Agent Bootstraps Identity

- Generates ephemeral DID linked to owner’s permanent identity

- Signs its public key using its hardware-anchored root

- Agent Requests Access to Service

- Prepares CB-PoP: signs request metadata, timestamps, hash of recent model inputs, and enclave measurement

- Attaches DID and enclave attestation proof

- Service Validates Request

- Resolves DID and verifies VC chain

- Confirms enclave integrity and CB-PoP freshness

- Checks smart contract for permission rules

- Access Granted

- Service encrypts data with agent’s public key (ensuring only that enclave can decrypt)

- Transaction is logged immutably with context metadata

Why It’s Better than OAuth

| Feature | OAuth 2.0 | CADA |

|---|---|---|

| Agent Identity | Static Client ID | Dynamic, Decentralized DID |

| Trust Model | Predefined Scopes | Runtime Context + Attestation |

| Token Security | Bearer | Ephemeral, Context-bound, Non-exportable |

| Privilege Model | Long-lived Access | Zero-standing Privilege |

| Revocation | Manual / Opaque | Smart Contracts, Observable Context |

I started to write some stuff last night in Rust, I'll get this up in Github in the next few days.

Generate a Decentralized Identity (DID)

use ssi::did::DIDMethod;

use ssi::did_resolve::DIDResolver;

use ssi::jwk::{JWK, Params as JWKParams};

use ssi::vc::URI;

fn generate_did() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let jwk = JWK {

params: JWKParams::OKP(ssi::jwk::OctetParams {

curve: "Ed25519".to_string(),

public_key: vec![],

private_key: Some(vec![]), // Generate ephemeral keypair

}),

..Default::default()

};

let did = ssi::did::did_key::DIDKey.generate(&jwk)?;

println!("Generated DID: {}", did);

Ok(())

}

Bind Key to Hardware (e.g. TPM or Nitro Enclave)

use tss_esapi::Context;

use tss_esapi::structures::{Auth, Public};

fn generate_tpm_bound_key() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let mut context = Context::new(Default::default())?;

let key_auth = Auth::try_from(vec![0u8; 32])?;

let public = Public::rsa_encrypt_decrypt_key(/* your key parameters here */);

let (key_handle, _) = context.create_primary(public, key_auth)?;

println!("Key generated and bound to TPM context.");

Ok(())

}

Create a Context-Bound Proof Token (CB-PoP)use chrono::Utc;

use ring::signature::{Ed25519KeyPair, KeyPair};

use serde_json::json;

fn create_cb_pop(agent_id: &str, model_digest: &str, enclave_measurement: &str) -> String {

let now = Utc::now().timestamp();

let token = json!({

"agent_id": agent_id,

"timestamp": now,

"context": {

"model_state_hash": model_digest,

"enclave": enclave_measurement

}

});

// Sign it using an ephemeral keypair inside enclave or bound to TPM

let keypair = Ed25519KeyPair::from_pkcs8(&get_private_key_bytes()).unwrap();

let signature = keypair.sign(token.to_string().as_bytes());

json!({

"token": token,

"signature": base64::encode(signature.as_ref())

}).to_string()

}Smart Contract

use ethers::prelude::*;

use std::sync::Arc;

#[tokio::main]

async fn validate_contract_permission(agent_id: String) -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let provider = Provider::<Http>::try_from("https://mainnet.infura.io/v3/YOUR_PROJECT_ID")?;

let client = Arc::new(SignerMiddleware::new(provider, Wallet::from(...)));

let contract = Contract::new("0xYourContractAddress", contract_abi, client);

let is_allowed: bool = contract.method::<_, bool>("isAuthorized", agent_id)?.call().await?;

println!("Access allowed: {}", is_allowed);

Ok(())

}